Okay, first, my new laptop had to go in for repair so I’m trying to blog from my phone. I have no idea how this is going to turn out. But I just discovered something that I wanted to share and I don’t want to wait for HP to do its thing. Hopefully this will go as well as the WordPress app assures me it will.

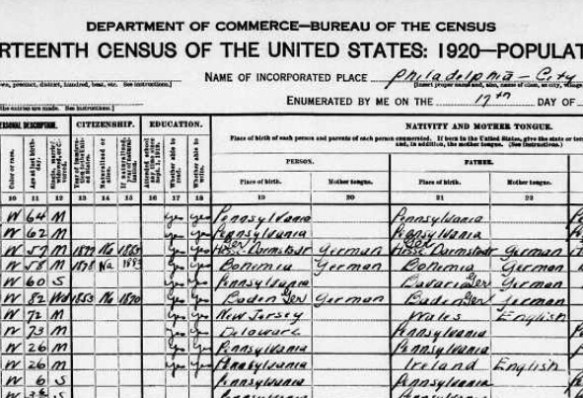

Today I want to talk about census records. The backbone of genealogical research. When I first started working on my family tree, censuses were pretty much the only widely available online records. Like most researchers, I spent years in those records, using their various details to fill in the blanks of my ancestors’ lives. And after all that time, I thought I’d seen every little weirdness the census records had to offer.

I was wrong.

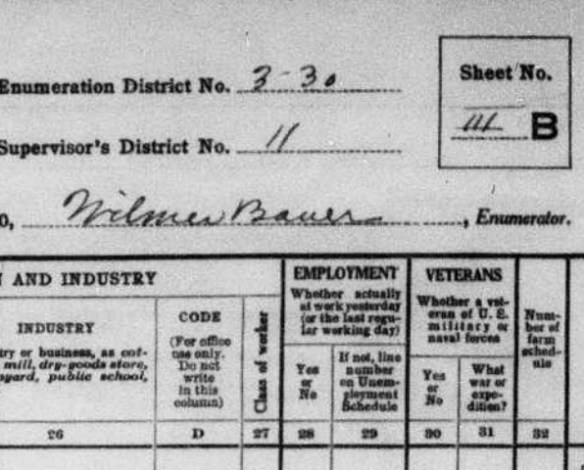

Recently, when I was recording a relative in the 1930 census in Delran, New Jersey, I came across this:

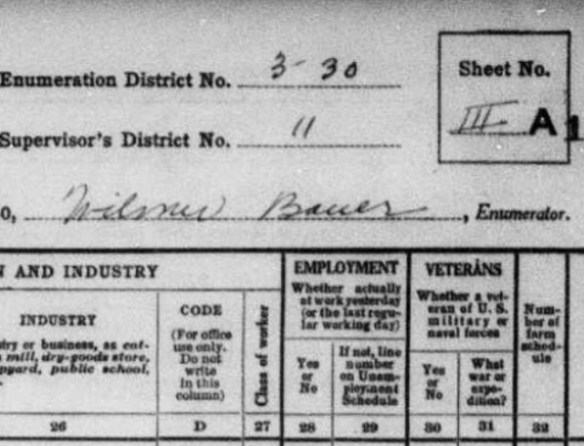

I was bopping along, writing my citation, inputting the page number, and . . . what?! For a while I just stared at it, wondering what number it could be. My brain was blank. To help me I moved back to the previous page:

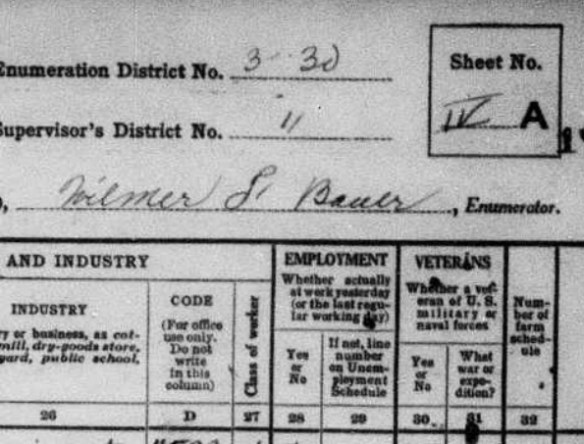

No, I still didn’t get it. So I checked the following page instead:

Wait . . . really? Were these . . .

Yes, they were.

Now for those readers unfamiliar with how the census worked in our past, townships were divided into enumeration districts and there was an enumerator, in this case Wilmer Bauer, assigned to collect and report the population details for each district. They canvased the neighborhoods and filled in these huge sheets with information for each and every person in their district. And they numbered their pages.

But here’s the thing. There are close to 2,000 people in my family tree. Almost all of those people appeared in at least one census, and the majority appeared in several. Which means I have searched, downloaded and cited thousands of census pages from across the country and the years. And Wilmer Bauer in Delran, New Jersey is the single, solitary enumerator I have ever seen number his pages with Roman numerals. So maybe you can understand why I stared at that III for so long, trying to figure out what kind of strange code it was!

In 1930 Delran (a little township in Burlington County) only had two census enumeration districts. Nettie Smith, who enumerated District 29, dutifully used Arabic numerals just like every other census enumerator I’ve come across in more than 20 years of using these records.

Why, Wilmer? That’s what I really want to know. What made this particular New Jersian (Jerseyan?) decide to take his 16 pages of Delran residents and stamp them with his Latin flair? Was he flouting the rules everyone else carefully followed?

As it turns out, the instructions to census enumerators for each decade of the census are available online at the Census Bureau web site. I recommend checking them out. They’re a surprisingly interesting read!

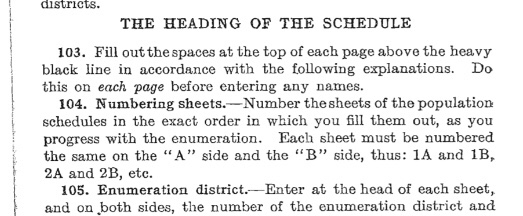

But for the purpose of answering my question, we’ll go straight to the 1930 section on numbering pages:

So . . . aside from matching your A side and B side, it doesn’t implicitly state that Arabic numerals must be used.

I like Wilmer Bauer. I like to imagine him making the choice to put his own stamp on his pages with those Roman numerals. To heck with the given example! To heck with how everyone else had ever done it in the history of the U.S. census! Wilmer was going to make his mark, darn it!

Maybe I’m being romantic. Maybe Wilmer always numbered everything in his life the Roman way and so didn’t think twice about doing it on his census pages. Either way, I suspect he was a interesting dude. And 88 years after he made that choice, he knocked me out of the rote of source citations and gave me something to marvel at. That’s pretty cool.

You do you, Wilmer Bauer.