One thing I’ve noticed during my years pursing genealogy: when someone outside the genealogy world discovers you’re researching your family tree, you can bet the first thing they’ll ask is whether you’re related to anyone famous. I’m always taken aback by the question, even though I get it so often. The quest for famous ancestors is so far from why I do what I do.

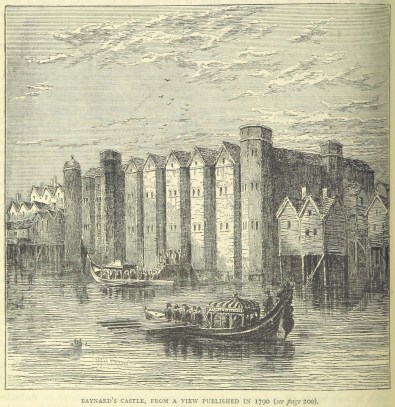

Now don’t get me wrong. It would be cool to discover I was descended from English royalty or Caribbean pirates. My mother has Baynards way back in her Maryland line, and there are rumors they might be descended from Ralph Baynard. You’ve probably never heard of him, but he built Baynard’s Castle, which stood near what is now Blackfriars in London. They tell you all about it on those Thames boat tours. He’s also the person the Bayswater area of London is named after. And, oh yeah, he crossed the channel with William the Conqueror and . . . conquered. Blasé as I’d like to be about famous connections, if I found real evidence that Ralph Baynard was my ancestor, you can bet they’d hear me squealing in Bayswater. But no, I’m not descended from anyone famous. That I can prove. Yet.

Baynard’s Castle – potentially my ancestral seat (if it were still standing . . .)

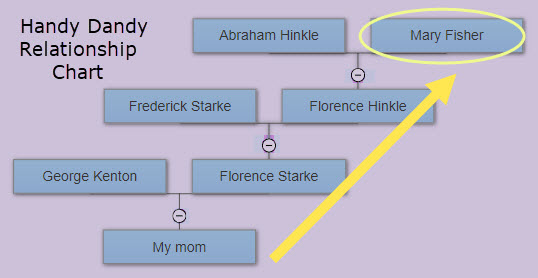

Connections to Norman conquerors aside, you know what keeps me at this day after day, and leaves me bubbling over with stories that I had to start a blog just to tell? The ordinary, everyday stuff of the past, and the people who lived through that stuff. That’s what I can relate to and what brings the past alive for me. So when people ask me what exciting ancestors I’ve discovered, I always tell them about Mary Fisher.

Mary Fisher was my second great grandmother directly up my female line and on the surface, she was as ordinary as her name. I don’t have any photos of her, or newspaper clippings about interesting things she did. She wasn’t associated with any important events. She lived, she bore children, she brought her family to Philadelphia to fulfill the timeline that would lead to me, and she died. But as is so often the case with family research, dig a little deeper and there’s . . . more to the story. (See what I did there?)

Mary was born in 1856 in Berks County, Pennsylvania, to George Fisher and his wife Catherine. The family first appears on the census in 1860 living in South Manheim township in Schuylkill County. Even by the standards of the time, George was on the low end of the socio-economic scale. Coal hadn’t completely taken over the region yet; most of George and Catherine’s neighbors were farmers and craftstmen. We find boat builders and shoemakers, railroad workers and bricklayers. George was enumerated simply as a laborer. His personal estate – everything he owned in the world – was valued at $20. When many of their adult neighbors, male and female, could read and write, George and Catherine could not. In 1860 Mary was only four years old, the eldest of three daughters. In the next few years two more girls were added to the family, and two passed away.

And then, sometime between 1860 and 1870, George disappeared. He probably died, as Catherine eventually remarried, but I’ve never found any evidence of a death. He may have died in the Civil War, but again, there are no records I can substantiate as his. What I do know is that in 1870 Catherine was enumerated in the nearby town of Butler as the head of her household of three girls, Mary, age fourteen, Susanna, who was six, and little Minnie, just three years old. Catherine was now the breadwinner, working as a housekeeper in someone else’s house. And we can infer that the housekeeper at the Fisher house – the person doing all the cooking and cleaning and child care – was 14-year-old Mary.

Two years later, at the age of 16, Mary Fisher married Abraham Hinkle, a 22-year-old coal miner. It was almost certainly a shotgun wedding.

Marriage Records of Christ United Lutheran Church, Ashland, PA

You see it, right? To steal a phrase, it’s a tale as old as time. Teenage girl, stuck at home caring for her younger siblings, which was a lot more work then than it is now. Finds a nice young man and sees the chance to be out from under mom’s thumb. If she has to work it might as well be in her own home where she’s in charge. The Hinkles weren’t rich, but they were well ahead of the Fishers. Mary wouldn’t have been the first girl to take the “oops” route out of her parents’ house and into her own.

Of course, all this is speculation. I don’t have an exact birth date for Mary’s oldest daughter, but her age is within the range that would make a pre-wedding pregnancy feasible. And it seems unlikely that with a full-time job and an 8- and 5-year-old to care for, Catherine would have let Mary go for anything less than absolute necessity. She was, after all, only sixteen.

There’s obviously no way to know what went on in Mary’s head, but that’s part of what makes it all so interesting to me. I can imagine her situation so easily. I knew girls in high school who took the same route Mary may have. It’s so familiar, even though it’s deep in the past. Mary was ordinary. What happened to her was common. But the details of her situation tease at my brain. The fact that I’ll never know the truth doesn’t keep me from coming back to her, over and over again.

And there’s more!

You know that saying, out of the frying pan, into the fire?

By 1880, eight years into her marriage, Mary had a husband in the mines all day and four children at home – none of them yet attending school. She probably had had a fifth in that same time period who didn’t survive. She would go on to have six more. Eleven children in a twenty-year span. Twenty plus years of somebody always in diapers, always nursing. Twenty years of pregnancy after pregnancy. I honestly can’t imagine surviving it, although of course millions of women did. I can imagine that Mary’s three oldest – all girls – had their own moments of teenage frustration when Mary pressed them into cooking, cleaning, and child care duty. But none of them took Mary’s way out.

Despite a number of pregnancies that makes my eyes cross, Mary lived to the ripe old age of 79. She and Abraham eventually took that huge family to Philadelphia – I like to think to get the boys out of the mines. I also like to think that Mary got to enjoy a couple decades of peace and quiet after all those years of toil. She passed away in 1935 in a little house on Wendle Street, cared for by . . . her younger sister Susanna. Full circle.

The house on Wendle St. where Mary lived her final years.

Mary Fisher is honestly one of my favorite ancestors. I think about her often. I wonder if she regretted the decision I like to believe she made. In the thick of motherhood, did she long for the time when she only had two little sisters to care for? Or did she love her husband and thrive on having her own family, huge as it was? That’s just another thing I’ll never know. Mary’s youngest daughter Florence – my great-grandmother – died when I was four and I don’t remember my own grandmother ever talking about her. So in a lot of ways she’ll always be a mystery to me. But mysteries are why we do this, right?

Every year I go to our Southern California Genealogical Society Jamboree – a national-level genealogy conference. In the course of the four days I talk to a lot of people. We chat before sessions or over lunches. Everyone wants to share about their ancestors. But in all the years I’ve been going, I couldn’t tell you one time someone told me about being related to someone famous. No, I hear about the little, quirky, everyday events they’ve discovered researching their absolutely ordinary ancestors. I hear about their Mary Fishers. And then I tell them about mine.

But what about poor Catherine, left with her full-time job and her two small children? Never fear! After she lost Mary she quickly found herself a husband – Abraham Hinkle’s older brother Frank. Making her her own daughter’s sister-in-law and making my pedigree chart very unhappy. But that’s a slightly less ordinary story for another day.